While imprisoned under the fascist rule of Benito Mussolini, Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci penned a collection of writings that would later be published as his “Prison Notebooks.” (1) Though these writings touch on many facets of the emerging neo-Marxist thought Gramsci represented, his exposition of “cultural hegemony” remains among his most enduring critiques of capitalist society. This lens divides capitalist culture into two parts: the base and the superstructure. Originally put forth by Marx, the base represents both the means and modes of production; the superstructure refers primarily to a society’s dominant ideologies. Where Marx believed that the inherent turmoil of capitalism would move the working class, or proletariat, to rebel against the superstructure, Gramsci instead focused his efforts on understanding why the revolution never materialized. In “Prison Writings,” Gramsci asserts that the capitalist class has successfully convinced the proletariat to take stock in the beliefs upheld by the superstructure. Rather than find issue with class disparity, exploitation, and alienation, the working class has instead adopted the interests of the bourgeois as their own.

Enter graphic design. Though nearly every society in global history has participated in the production of graphic artifacts, graphic design as a prominent commercial practice emerged during the Industrial Revolution. As advances in print technology presented opportunities for increased circulation by those with the means to publish, from the colonial fervor rose the first incarnation of the United States’ advertising industry. While graphic design today is positioned adjacent to the fine arts, it’s origins are unavoidably steeped in colonialism and racial capitalism. Western-centric design histories present the Bauhaus as the first proper design school; though trade-oriented print production demanded graphic design skills long before the German institution’s opening, the Bauhaus remains a celebrated representative of design’s purportedly transcendent potential. (2) Built upon the foundation of the prior Weimar Arts and Crafts School, Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus defined itself as an unprecedented and dynamic learning institution; it boasted of its ambition to marry the arts and crafts in pursuit of the next wave of beautifully designed objects.

The market-first legacy of the Bauhaus remains embedded in the operational models of contemporary design school. Students attend a four-year undergraduate program, are equipped with the technical skills to produce graphic design work for the market, and leave one institution in search of the next. Graphic design becomes a high-functioning tool of the culture industry; from bus stops to billboards to t-shirts to gig posters, our visual culture is produced and provided by the capitalist class—these artifacts maintain the superstructure’s dominance, the subordination of the proletariat. Aesthetic alibis cloak long-formulated corporate models that ensure all incoming revenue further exacerbates nationwide wealth inequality; petite bourgeoisie graphic designers masquerade as an elite “creative class.” As present realities outstrip the projected dystopias of decades past, graphic designers are among the many who must face the increasingly-opaque-and-odious machine (3) of late capitalism.

During my time studying within Pratt Institute’s Communication Design program, the teaching has largely failed to recognize the economic inferno underpinning the curriculum’s learning objectives. In it’s near-total lack of criticality toward the socioeconomic positioning of design professions, Pratt’s current Communication Design track openly embraces neoliberalism and its accompanying existential threats. By decoupling both design labor and its resultant artifacts from their larger societal roles, a depoliticized design education offers a slew of trade-like courses that walk students through the motions of rebranding the next quasi-philanthropic Bloomberg initiative. (4) In the current context of Pratt’s undergraduate graphic design program, discourse that diverges from the curriculum’s neoliberal core struggles to provide more than critically-impeded lip-service.

In looking toward curricular reform, a pedagogical model centered around ethics and criticality provides a potential path forward. An ethical lens acts as a tool for a broad range of considerations. It encourages the graphic designer to think about their own ideologies as removed from those passed-down by the superstructure. It requires the practitioner to face the dissonance between their belief systems and the confines of the spaces they operate within. An ethical program would be multi-pronged; where interventions within the current curriculum are declawed by their contextual limitations, an institutional overhaul reboots a system that has been blinded to its own weaponization by the reward of capital.

Though there are infinite configurations for an ethics-first design education, I am interested in how a three-piece restructuring might change the orientation of the studying practitioner. These three tenets are as follows: one, a graphic design program that avoids historical linearity and substitutes a critical lens for the standard of celebration; two, a graphic design program that treats the field as a liberal art, thus necessitating a broader range of study that better positions design as labor under capitalism; three, a graphic design program that centers its studio work around counter-capitalist modes of production. Even beyond this, a larger question looms: in re-ordering this model of learning, does the institution remain necessary?

As it is taught today, the history of graphic design serves to normalize and celebrate colonialism. Textbooks like “Meggs’ History of Graphic Design” (5) depict a linear trajectory in which every itemized moment within graphic design history becomes a stepping stone to the present day; the consequence awarded to any given juncture in this lineage is derived only from the ease with which it can be presented in celebration of the Western canon. Meggs claims that the Industrial Revolution is to be thanked for an expanded middle class, implying the existence of a benevolent—and clearly fictional—capitalism that sympathetically lowered its bootstraps to the proletariat. Industrialization should be thanked for bringing us fat face letterforms to adorn colorful show bills but never considered critically for the way printed pamphlets allowed the colonial United States to annex much of North America. (6) The very idea of the International Typographic Style subsists on colonial mythologies—more accurately described as the Post-War Swiss & German Typographic Style, the privileging of European systems of information organization as a globally superior vernacular provides a representative microcosm for the dangerous narratives that drive contemporary design historiographies.

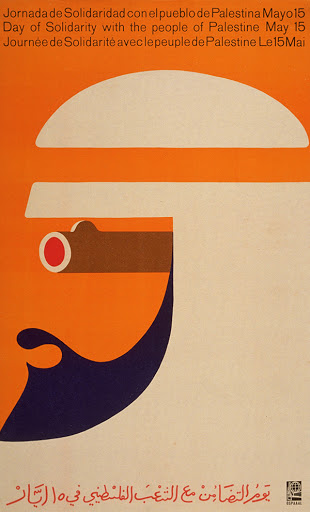

This Othering permeates today’s textbooks; in Meggs’ “History,” chapter 21 presents “The Third-World Poster.” Here, the world of Other is specified as Latin America, Asia, and Africa. There is no substantial explanation given for their assigned status of “third”—the label is inherited from a global dichotomy that is only able to divide the world by “capitalist democracies” and the “communist block.” The work from beyond this reductionist division is further simplified into either “spontaneous expressions, crude folk art” or “created by accomplished artists.” The unifying factor, Meggs posits, is that these posters have an agenda; though not categorically incorrect, this Othering performs to demarcate anti-capitalist work as agenda driven without acknowledging the embedded agendas of market-driven design. Meggs’ inability to consider design beyond capitalism is put on clear display when he states the two constituencies that “third-world” design addresses: the political audience of its “native” land and the secondary demand for these artifacts in the marketplaces of capitalist democracies. Even when writing on radical anti-imperial labor movements, this strain of history stretches itself to embed Western capitalism as a sympathetic spectator, an absolute erasure of the actively anti-revolutionary role the United States has played across the globe. It is in this 2-page section that OSPAAAL receives its only mention. (7) The organization, founded in 1966 Havana, has produced decades of movement-oriented visual ephemera alongside its “Tricontinental” magazine. However, in order to maintain Western-centricity, Meggs is quick to disarm OSPAAAL’s singular mention by informing readers that its visual language emerged from a lack of artistic tradition. It does not go far enough to describe this historiography as passively non-inclusive when it repeatedly presents a commitment to maintaining the division between the subaltern Other and imperial capitalism.

Expanding that which constitutes undergraduate graphic design studies to include more requisite liberal arts courses would force designers to step down from their pedestal and process the wider social relations of their work. Though the liberal institution’s discourse has grown to welcome the lambasting of individuals like Jeff Bezos, the dialogue stops short of further investigation into the systems that allow such gross amassment of capital and exploitation of labor. Critical cultural studies would equip students with a better understanding of the ways in which their involvement in larger corporate machines upholds systemic oppression. Today’s graphic designer moves into a market as defined by information as it is wrought by conventional (tangible) commodities. McKenzie Wark labels this as an information political economy, a heavily-mutated capitalism that has given birth to a new vectoralist class with power beyond the traditional material capitalist class. (8) Graphic designers act as the estheticians of consumer-facing commodities and services, and the accompanying pedagogy must imbue the profession with the burden of its responsibilities. While revised historiographies reorient the past performances of graphic design amidst a more equitable global history, a program less constrained to the lingering trade-like ethos creates space for new modes of practice and dialogue that reflect the urgent need for reparatory action.

Counter-capitalist pedagogy implicitly concerns itself with ethics by liberating graphic design from the confines of commodity and/or information production. Opening up the breadth of design education would not necessarily reduce the formal output of the student—though this possibility ought not to be struck down on principle alone. Even talk of decolonial studies—discourse increasingly permitted within the university context—is done a massive disservice when those studying it are encouraged to approach these studies as impetus for artifact production. Object-obsessive design curricula ingrains within students the need for every exploration or interest to lead toward a document of sorts—ideas and curiosities are only reified when they amount to a polished form. In recent decades, the field has exhibited new interest in the designer as anything-but. Michael Rock’s “Designer as Author” (9) nudges one to consider why auteur status remains so coveted, why the designer yearns to flex their agency through transcendence of their social context. No field of study can exercise its full scope when simply appended to the domineering title of designer. If traditional institutions for design education are unable to meaningfully dissociate critical studies from commercial training, the need to build new spaces for new learning burns bright.

The final tenet of this initial proposal regards a restructuring of the studio curriculum, the credits that most directly harken back to the need for graphic design education to provide trade skills. For most programs at Pratt, the fall semester of a student’s sophomore year introduces them to their first major-specific core classes. Studio courses under the Communications Design umbrella revolve around sets of “Goals” and “Objectives.” (10) A retrospective analysis of these learning outcomes charts a six-semester program in which students are trained to concept and execute design solutions at the behest of a client. At present, these studio courses lean into the notion of “design thinking.” Popularized by industrial design firm IDEO in the late 1990s, design thinking positions the designer as visionary extraordinaire; gathered around Post-it filled walls, design think-tanks declare the newest strategies with which to streamline capitalism. In a 2018 promotional video for IDEO’s online education initiative, design thinking is broken into its three guiding factors: desirability, feasibility, and viability. There is little attempt here to obfuscate design thinking’s enthusiasm for ever-accelerating capitalism. An IDEO blog post from 2014 titled “Capitalism Needs Design Thinking” (11) captures a conversation between company chair Tim Brown and Roger Martin, then-director of the Martin Prosperity Institute; though meandering, the dialogue paints a vivid picture of the design thinking ethos. During the latter half of the conversation, Brown proclaims, “You think about the retail environment, where classically retail workers are poorly paid and have little job security, but if those same retail workers are able to use the tools of design thinking to really understand the needs of the customer, constantly think around how the store environment might be better able to serve those needs and, therefore, make business far more successful because of it.” The core delusion of design thinking is that a more efficient capitalism results in a more empowered working class. There is little more to see here than a vaguely-liberal rehashing of Reaganomics—design schools must prove that they can do better.

With the Bureau of Labor Statistics projecting the existence of over 250,000 graphic design positions in the United States, the clear reality remains that most designers will find themselves greasing the gears of Corporate America. (12) A model for education with its sights trained on commercially-applicable coursework surrenders to this reality, discouraging any ambition of radical critical practice. Trade glossies like Ad Age and their “A-List” (13) celebrate the success of enormous multinational ad campaigns, assuring those within the field that their work need not be critical or challenging as long as it commands a quasi-objective understanding of advertising ingenuity. As attractive as the agency pipeline may be to an institution’s post-graduate statistics, one must not forget that school days are, in fact, free from the need to bend at the knee to client directives. Learning must concern itself with critical speculation rather than a silent embrace of the powers that be. How would alternative contexts condition the ways in which young designers learned to approach work? Imagine a curriculum in which students were tasked to design under the pretext of communism; how would refutation of free-market ideologies inform the resultant work? If designers were tasked with producing a speculative plan for bartering their work and surviving without dependency on fiat currency, how would their understanding of graphic design’s myriad performances shift? The studio course—and the institution at large—only stands to grow by delivering its scope without rolling over for visiting agency critics.

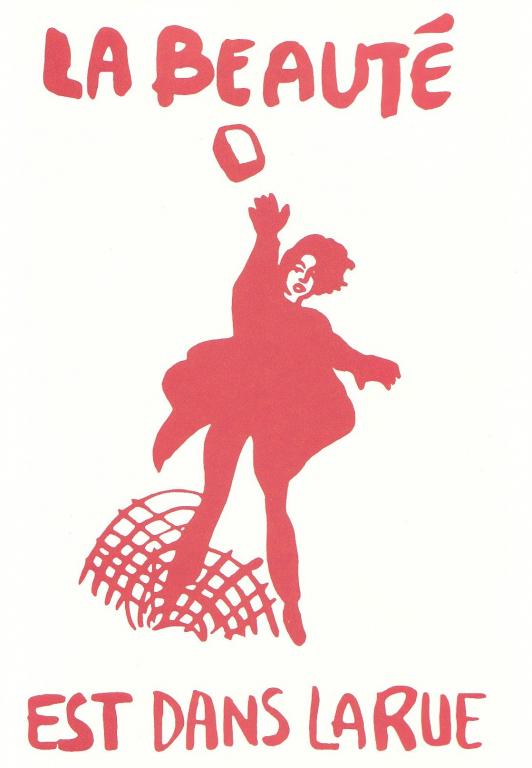

Institutional critique cannot be prescribed without acknowledging the limitations of the demanded institutional reform. Most American design schools are not state-funded; they stay afloat by promising a path into industry. A deep commitment to American exceptionalism guarantees that the powers of academia are never challenged by structural resistance; there is no unguarded window through which the operational ethos of a school like the Sandberg Instituut may creep in. With such a dearth of social programs in the US, it can become difficult for the student and institution alike to look beyond the profit-motive. Nonetheless, a school’s student body represents the greatest holding of power among the forces of the institution. In the 1960s, the Free Speech Movement (14) tore through Berkley by way of an engaged campus constituency, and massive student action filled the streets of Paris. (15) When the youth reaches critical mass, there is little that can be done to quickly disarm them; until then, it may be worthwhile to move beyond the compromised offerings of the design school in search of more critical discourse.